Montessori Has Failed

and what we can do about it

The Montessori Movement has failed.

Of all education models, Montessori is the only one that has profoundly fallen short of its stated goal.

The traditional model of education has provided a free appropriate public education (FAPE). Reggio has wonderful examples of child-led and project-based learning. Homeschooling has continued to grow since the pandemic.

But only Montessori has failed. The movement has failed not because it’s ineffective, but because we have lost sight of its most radical and moral purpose: PEACE.

I was reminded (again) of this powerful mission while reading Erica Moretti’s book The Best Weapon for Peace. In it, she writes:

“Maria Montessori sought to develop a pedagogy that would guide children to become balanced human beings who could ultimately end war.” -pg. 79

Moretti is writing about Montessori’s response to fascism and the wreckage of two world wars. A century later, our wars look different but the need for peace education has only intensified.

Peace today is not just the absence of war. It’s also the ability to love differences, to cherish interdependence, and to repair harm in community. These are all lessons Montessori classrooms are uniquely positioned to teach.

*Disclaimer*

I should pause here to emphasize something: this is not a hit piece. I write this because Montessori education is my calling. My cosmic task (iykyk). I fully drank the Montessori koolaid many years ago, so this comes from a place of deep love and appreciation for the Montessori Model. I truly believe, like the good Doctor said, Montessori education is the “best weapon for peace.”

But I also believe, as James Baldwin said, “I love America (Montessori) more than any other country (pedagogy) in the world and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize it perpetually.”

Full disclosure: this disclaimer is for my mother, a passionate career Montessorian, who I hope doesn’t disown me after reading the following.

(Not Yet) Best Practices

Montessori has made significant contributions to the advancement of best practices in education. So many “new” fads have origins in Montessori practices. Differentiated instruction, hands-on materials, nature-based learning. Trends in today’s educational journals were influenced by Montessori principles a hundred years ago.

But what has the Montessori community learned from the newest research on the science of peace education and peacemaking?

For many years, I led the Montessori Model United Nations (MMUN) club for our school. MMUN is an incredible supplemental program designed to “inspire and empower youth to become global citizens by engaging them in a simulated UN conference to solve world issues through education, collaboration, and a focus on peace.” Yet supplemental is exactly what it remains. It’s an optional program for the few, rather than an essential curriculum for all.

Montessori’s famous quote, “Preventing conflicts is the work of politics; establishing peace is the work of education,” is not unclear to me. This work is not simply an invitation or an opportunity. It can’t be limited to a handful of students. It can’t be a club. It’s a mandate for all of us.

This mandate requires the Montessori community to intentionally and explicitly incorporate modern peacemaking science into the foundations of everything we teach children and families, from prenatal development to adolescence. In traditional education, this work is typically the domain of higher education. However, Montessori educators have the opportunity not only to articulate but also to implement a vision of education that begins immediately and incorporates another foundational principle of Montessori’s work: the empowerment of youth.

“I believe that children are our future.”

Dr. Montessori wrote that “If we are to reach real peace in this world...we shall have to begin with children.” I recently wrote about my first-hand experience of students being the most important drivers of peaceful change. Over and over again, I’ve witnessed young people practice kindness, creatively solve problems, and participate in restorative circles far better than adults. Despite this competence, adults actively prevent young people from gaining access to political power. Maria Montessori knew early on that children and adolescents were a marginalized group, stating plainly:

“The laws of social justice did not consider the child. Democracy, the democracy for which we have fought yet another war, the democracy which governs most of the world, does not exist for the child.” -Citizen of the World, p. 118

We now have decades of research affirming what Dr. Montessori saw so clearly: young people are excluded from shaping the world they live in. In 2015, the United Nations adopted Resolution 2250, calling for youth participation in peace and security efforts at all levels. The follow-up study, which engaged over 4,000 young people worldwide, revealed the sobering truth that youth experience what they call the “violence of exclusion.”

This isn’t the violence of war. This is the quiet, structural, and psychological violence of being shut out of decision-making.

The study found that this exclusion is “deeply rooted in the reciprocal mistrust between young people, their governments, and the multilateral system.”

Maria Montessori’s insight was prophetic. She understood that children and adolescents are not passive recipients of education, but rather marginalized citizens living in societies not designed for them.

True peace, then, depends on dismantling the systems that silence youth and replacing them with communities that listen, trust, and empower them to lead.

“Do we believe and constantly insist that cooperation among the peoples of the world is necessary in order to bring about peace? If so, what is needed first of all is collaboration with children.... All our efforts will come to nothing until we remedy the great injustice done the child, and remedy it by cooperating with him. If we are among the men of good will who yearn for peace, we must lay the foundation for peace ourselves, by working for the social world of the child.”

-Maria Montessori, International Montessori Congress, 1937

Shifting Focus

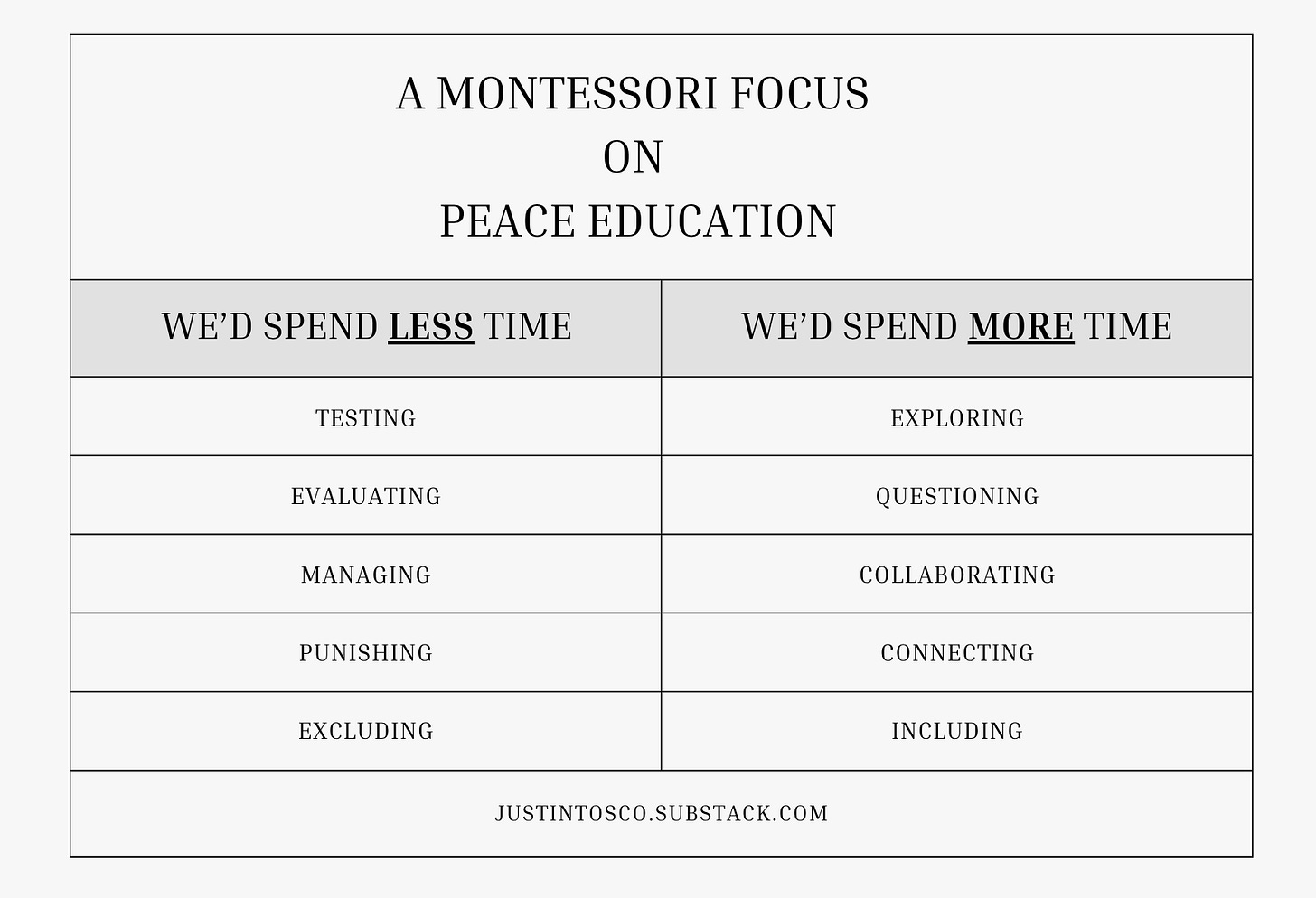

There are certainly elements of peace education that have become more ubiquitous in schools (eg. mindfulness, global citizenship, social-emotional learning, restorative practices), but only Montessori education has as its first principle peace education specifically.

What would it look like for every Montessori student, teacher, advocate, and organization to stay singularly focused on peace education, led by young people, as the north star for every action we take? If peace truly guided our classrooms, our calendars, our budgets, our curriculum, and our conversations, our priorities would look very different.

Where To Begin

Besides consistently reorienting ourselves with Maria Montessori’s writings on peace education, we should also look to expert leaders and organizations that research, resource, and enact the work of peace education.

Paulo Freire was seminal in my own orientation to liberatory education. I’ve also learned from Johan Galtung's writing on the distinction between Negative and Positive Peace, Elise Boulding's emphasis on the importance of women in the peace process, and Jonathan Kozol's exploration of the political inequalities affecting American school systems.1

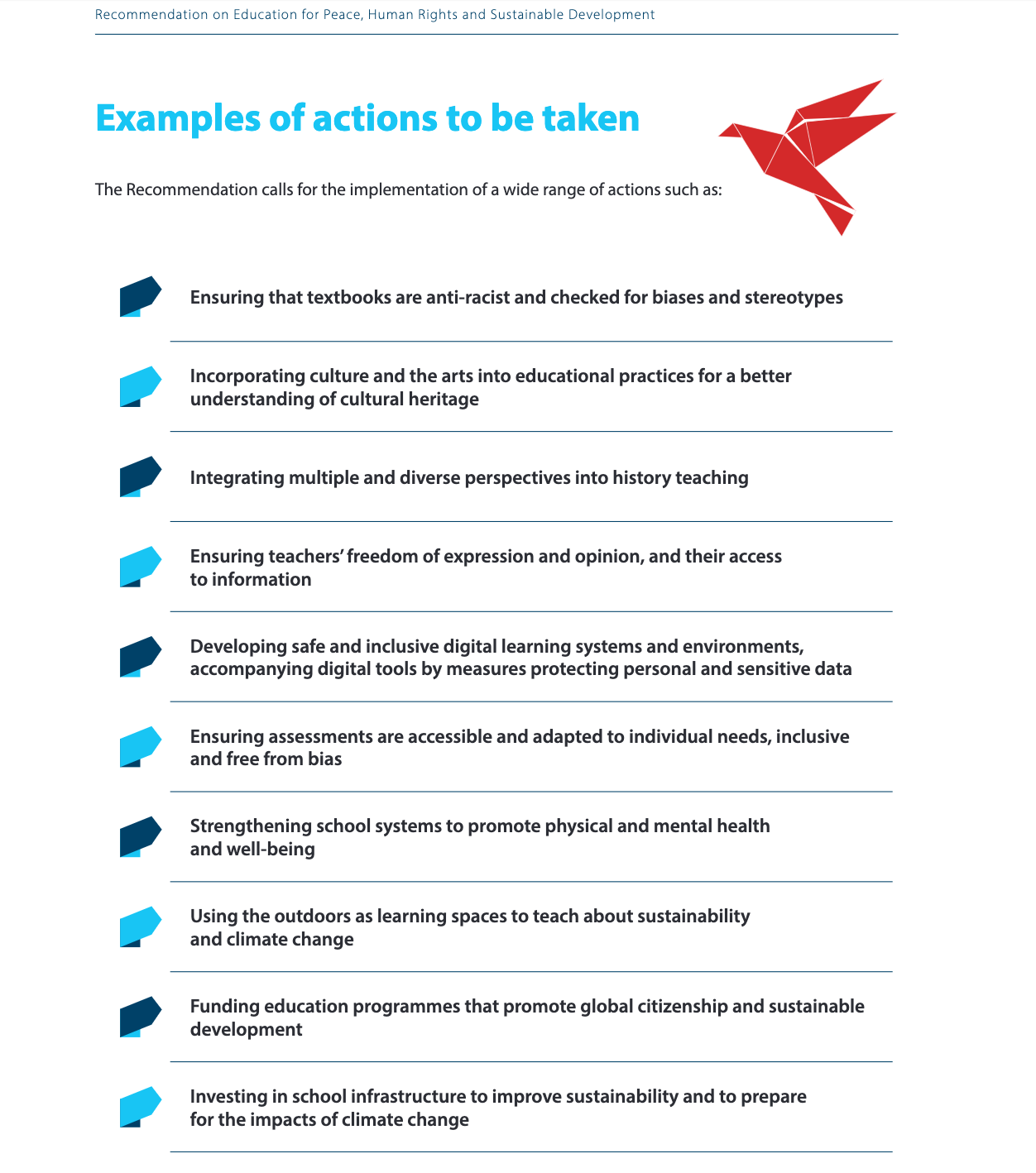

A vital resource is UNESCO’s Recommendation on Education for Peace, Human Rights and Sustainable Development. It is the “only global standard-setting instrument that lays out how education can and should be used to bring about lasting peace and sustainable development.” This resource would be a great starting point for schools, educators, and policymakers seeking practical steps to take.

In addition, we should ask:

How many school meetings include student voices in decision-making?

How does our budget prioritize peace curriculum over test prep?

How do our discipline practices choose restoration over punishment?

How have we incorporated the most recent research on peace education?

The work of peace begins with these daily, unglamorous choices. This work will be uncomfortable. It will require us to cede authority, question traditions, and acknowledge that our systems often prioritize adult needs for control over children’s needs for liberation.

No doubt, achieving Montessori’s mission is a long-term commitment. It will take many years. And many of us. After all, “An education capable of saving humanity is no small undertaking.”

Maria Montessori didn’t set out to create better students. She set out to create a better humanity.

That work remains unfinished, and it belongs to us now.

What essentials am I missing? Comment with your own recommendations.

thank you so much for talking about it, ive been telling my coworkers the same .. i will now share this with them .. so that they know im not the only one lol people get so mad when you talk about the crapy expensive school scams

Hello Justin,

Beautiful piece. I will add to the chorus that it made me reflect on our own practices, particularly concerning your statement that the Montessori approach has failed.

However, I feel there is currently too much focus on affective education, and too little dedicated effort to improving effective education. This improvement could be done through concrete actions such as: focusing on material usage in the classroom, encouraging action research from teachers, and including constructivist approaches that enhance joy, motivation, and inclusion for both teachers and students, such as Socratic inquiry, group-based learning, and projects.

In essence, teaching communication through the usage of constructivist approaches is spot on. To develop peace, we as teachers must include more constructivist practices that highlight the resources you shared. I think this will enable people to learn and understand other positions, not with disdain or worry, but constructively, where they feel heard, empowered, and capable of constructive engagement.

Cheers!